Major Tetrachords

Half Steps and Whole Steps

Before we can understand scales and tetrachords, we first need to understand half steps and whole steps.

Half Step The smallest pitch change in common practice western music.

Movement of one piano key up or down or one guitar fret up or down.

Whole Step Equal to two half steps.

Half Step

In most cases a half step will move you from a note name without an accidental to a note name with an accidental (D to D♭ or D to D♯ ) or visa versa.

The exceptions occur between E and F and B and C.

In these two places the natural notes are a half step apart so that moving a half step up from E gives you an F and a half step down from C gives you a B.

When working with a staff it is very important to remember where the half steps occur.

A sharp moves a note up one half step and a flat moves a note down one half step.

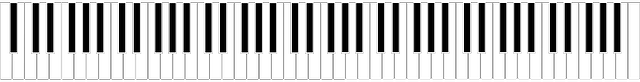

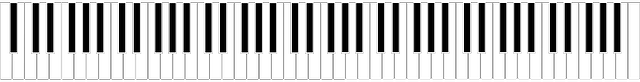

Notice how this is visually evident on the piano keyboard.

The white keys show the natural notes and the black keys show the accidentals.

D♭

D♯

D

D♭

D♯

D

The absence of black keys between E and F and between B and C show that there is only a half step between these notes.

B

C

E

F

B

C

E

F

Whole Steps

A whole step is equal to two half steps.

On a piano it will be two keys up or down and on a guitar it will be two frets up or down.

In most cases a whole step will move you from a note name without an accidental to another note name without an accidental (D to E or D to C).

The exceptions again occur between E and F and between B and C.

In these two places the natural notes are a half step apart so that moving a whole step up from E gives you an F♯ and a whole step down from C gives you a B♭.

To review Note Names see The Treble Clef and The Bass Clef.

To review Accidentals see Understanding Accidentals.

The key to telling the whole steps and half steps apart is knowing where the half steps occur in the musical alphabet.

Major Tetrachords

Major Tetrachord Bottom four notes of a major scale.

Almost all common practice music is built using scales.

The major scale is the most common scale in Western music.

Most scales are built up of intervals of half and whole steps.

Before learning the major scale we will first begin by learning the major tetrachord which is the bottom four notes of a major scale.

There are three rules to building a major tetrachord:

- The name of the tetrachord is the first note in the tetrachord.

- The notes are consecutive ascending letter names in the music alphabet. (Remember that after G the letters begin again with A.)

- The major tetrachord is constructed by using whole and half steps in this order: Whole-step, Whole-step, Half-step.

Example: D Major Tetrachord

- The name of the tetrachord is the first note, therefore it begins on a D.

𝅘𝅥

- Four consecutive ascending letter names starting with D: D, E, F, G.

𝅘𝅥

𝅘𝅥

𝅘𝅥

𝅘𝅥

- Add accidentals, if necessary, to form a series of whole-step, whole-step, and half-step. D to E is a whole-step. No accidental needed.

E to F is only a half-step, so we need to add a sharp to the F to make it a whole step. F♯ to G is a half-step, so no accidental is needed.

Notice that The 3rd note is an F♯ not a G♭ because the letter names need to be consecutive letters of the alphabet (see step 2).

𝅘𝅥

𝅘𝅥

𝅘𝅥

𝅘𝅥

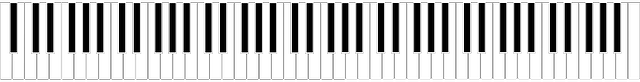

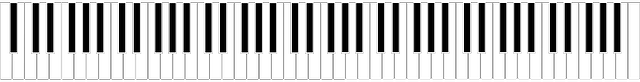

Most people find it easier to understand if they see it on a piano keyboard. You may want to read step 3 again while looking at the keyboard.

D

E

F♯

G

D

E

F♯

G